Milwaukee Freeways: Park Freeway

The Park Freeway in Milwaukee was one of the most complex and controversial projects in the city. Until 2003, the Park was a partially-constructed, partially-cancelled and never-finished freeway in three segments. While the freeway was not featured in the earliest expressway and freeway plans for Milwaukee, it became a key part of the final 1950s and 1960s system.

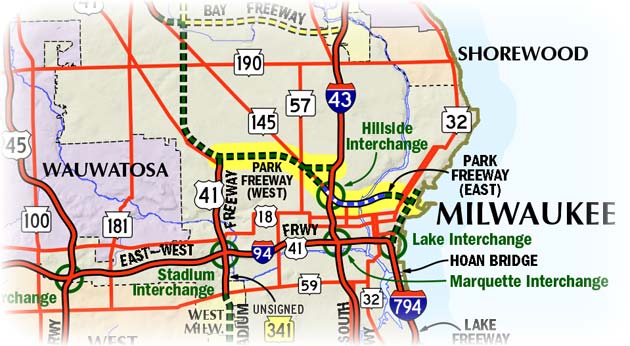

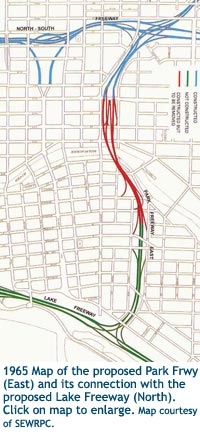

As originally conceived, the Park Freeway was to have begun at the Lake Freeway at an interchange in Juneau (now Veterans) Park on the northeast corner of downtown and proceeded westerly across the north side of downtown to a junction with the North-South Freeway at the Hillside Interchange. This portion was later referred to as the Park Freeway East or, more simply, the "Park East." From the Hillside Interchange, the "Park West" was planned to continue northwesterly along the Fond du Lac Ave corridor before bending westerly again paralleling North Ave to the south to an interchange with the Stadium Freeway near the intersection of Lisbon & North Aves. The so-called "Park West" was called the North Avenue Expressway in the original 1950s freeway plans, but renamed as part of the Park Freeway in the 1960s.

The first organized opposition to a Milwaukee area freeway came in September

1965 at a public hearing for the Lake Freeway through Juneau Park in downtown

Milwaukee. This segment of freeway would have stretched between the eastern

ends of the Park Freeway (East) and the East-West

Freeway and made up what

became known as the "Downtown Loop Closure Freeway." The battle

waged on until 1971 when the opposition to the freeway through Juneau Park

obtained a court injunction against the project which was upheld by the State

Supreme Court two years later. Thus, the Lake Freeway north of the Lake Interchange

with the East-West Freeway faded into history and the fate of the stub-ended

Park Freeway (East) was sealed, albeit thirty years later.

The first organized opposition to a Milwaukee area freeway came in September

1965 at a public hearing for the Lake Freeway through Juneau Park in downtown

Milwaukee. This segment of freeway would have stretched between the eastern

ends of the Park Freeway (East) and the East-West

Freeway and made up what

became known as the "Downtown Loop Closure Freeway." The battle

waged on until 1971 when the opposition to the freeway through Juneau Park

obtained a court injunction against the project which was upheld by the State

Supreme Court two years later. Thus, the Lake Freeway north of the Lake Interchange

with the East-West Freeway faded into history and the fate of the stub-ended

Park Freeway (East) was sealed, albeit thirty years later.

The first portion of the Park Freeway to be completed and opened to traffic was the segment from the Hillside Interchange where it met the US-141/North-South Freeway easterly to 4th St on the north side of downtown in 1968-69. Unknown to anybody at the time, but this segment represented half of the entire freeway that was ever to be completed.

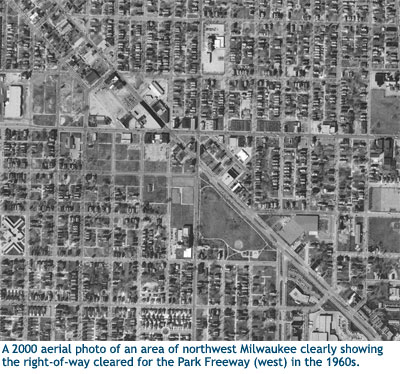

While the "Downtown Loop Closure" debate ended up causing the easternmost end of the Park Freeway to never be built, the debate west of the North-South Freeway was to be even more impassioned. The first three-quarters of a mile of freeway were just opening east of the North-South when the last of the land and homes for the Park Freeway (West) were being acquired and the residents evicted in 1969. The process by which the removal of residents from the path of the proposed western extension of this freeway is what spawned some of the first voracious protests and opponents, largely due to how the evictees were being treated and the condition of the replacement housing—where available. Work on the "Park West" was just ramping up at the tail end of what some call the "Freeway Era" in Milwaukee, when opposition was minimal and progress came at a dizzying pace. Oftentimes the concerns and needs of those displaced by the freeway projects were unfortunately not considered, laying the foundation for the canceling of many dozens of miles of freeways in the Greater Milwaukee area.

In

his book "Greater

Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View," Richard W. Cutler notes that freeway opponents gained a very

useful tool courtesy of the federal government in 1969: the National

Environmental Protection Act, or NEPA. Says Cutler: "They [the opponents] brought

suit in federal court claiming that an environmental impact statement had

to be prepared under NEPA before construction could commence. The started

suit notwithstanding the fact that before the legislation was enacted

in 1969, 99 percent of the land had been acquired and 1,590 homes had

been cleared at a cost of $22 million. On June 2, 1972, just days before

a $6 million construction bid was to be let, U.S. District Judge John Reynolds

restrained the letting of contracts, ruling than an environmental impact

statement had to be prepared before construction could commence."

In

his book "Greater

Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View," Richard W. Cutler notes that freeway opponents gained a very

useful tool courtesy of the federal government in 1969: the National

Environmental Protection Act, or NEPA. Says Cutler: "They [the opponents] brought

suit in federal court claiming that an environmental impact statement had

to be prepared under NEPA before construction could commence. The started

suit notwithstanding the fact that before the legislation was enacted

in 1969, 99 percent of the land had been acquired and 1,590 homes had

been cleared at a cost of $22 million. On June 2, 1972, just days before

a $6 million construction bid was to be let, U.S. District Judge John Reynolds

restrained the letting of contracts, ruling than an environmental impact

statement had to be prepared before construction could commence."

Construction on the "Park West" immediately ground to a halt while the pro- and anti-freeway forces began a fight in a variety of venues, including municipal, county, regional and state government, as well as in the arena of public opinion. Meanwhile, the second segment of the "Park East" was completed and opened to traffic in 1971, beginning at 4th St and continuing easterly across the Milwaukee River to a "temporary" ending at Jefferson St, although all traffic used the ramps to and from Broadway and Milwaukee Sts, with the freeway from there east to Jefferson consisting of stub end for the continuation of the highway toward the cancelled Lake Freeway.

Nearly three years after the halting of all work on the Park Freeway West, the public hearing on the court-ordered Environmental Impact Statement for the portion of the freeway from the I-43/North-South Freeway westerly to the Stadium Freeway North was held on May 13, 1975. While a few prominent supporters of the project spoke out in favor of completing the freeway as planned, most area residents spoke out in opposition. Even with the opposition, the EIS was completed at the state level and forwarded on to the federal government for approval. In January 1977, the FHWA rejected the Park West EIS noting there was "significant opposition on many fronts" and the due to the cancellation of the Stadium Freeway North earlier in the decade, any freeway in the Park West corridor would be of little utility.

With the federal rejection of the Park Freeway West EIS in hand, Governor

Patrick Lucey appointed a "Park Freeway West Task Force" later

in January 1977 to come up with a process for the disposal of the acre after

acre of vacant and unused right-of-way cutting across the neighborhoods of

northwest Milwaukee. The members of the task force, rather expectedly, recommended

that the freeway right-of-way be sold for housing, although twenty years

later vacant parcels in the former right-of-way still remain empty and undeveloped.

With the federal rejection of the Park Freeway West EIS in hand, Governor

Patrick Lucey appointed a "Park Freeway West Task Force" later

in January 1977 to come up with a process for the disposal of the acre after

acre of vacant and unused right-of-way cutting across the neighborhoods of

northwest Milwaukee. The members of the task force, rather expectedly, recommended

that the freeway right-of-way be sold for housing, although twenty years

later vacant parcels in the former right-of-way still remain empty and undeveloped.

A similar fate met the similarly-cleared right-of-way for the Park Freeway East between Jefferson St and Veterans Park on the north side of downtown. In 1981, legislation officially removed the un-built portion of the "Park East" from the State Trunk Highway System in a process called "de-mapping." After sitting fallow for two decades, the right-of-way in this area was also sold off for redevelopment, including the Eastpointe Commons, built by the Mandel Group.

The 1980s were a decade spent either removing vestiges of the un-built portions of the Park Freeway or attempting to remedy some of the various never-constructed connections and stub ends. Originally, a separate "leg" of the Park Freeway West was to have connected that freeway to the I-43/North-South Freeway running between Lloyd and Brown Sts (parallel to North Ave) between Fond du Lac Ave and I-43. Several stub ramps and an unused overpass over the North-South were constructed anticipating the never-built freeway. In the mid-1980s, this partially-built interchange was completely removed as was the unused overpass. Also in the mid-1980s, a connection was made between the Hillside Interchange, where the North-South and Park Freeways intersected, and Fond du Lac Ave. The several stub ramps from the Hillside Interchange were reconfigured and extended to feed directly into Fond du Lac Ave at Walnut St to allow better access in the area. (At that time, the STH-145 designation was extended down Fond du Lac Ave from 20th St and onto the Park East to Milwaukee and Broadway Sts, then southerly via that one-way pair to a new terminus in downtown Milwaukee.) Finally, in the late-1980s or very early 1990s, the dead-end stubs at the eastern end of the Park East were connected with Jefferson St a few hundred feet to the east at an at-grade intersection. This last action greatly increased the utility of the Park East and made use of the last several hundred yards of the freeway which had sat unused since 1971.

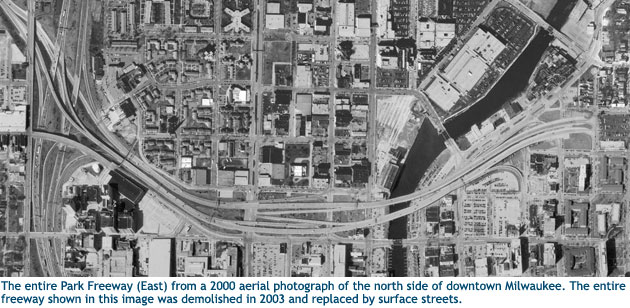

One could say the fate of the Park East was sealed in 1988 when former Milwaukee Mayor John O. Norquist was elected. Described as a "fiscally-conservative socialist," Norquist was also admittedly anti-freeway and while his early attention was focused on the I-794/East-West Freeway, he came to see the dangling stub freeway across the north side of the downtown area as an eyesore and a barrier to redevelopment efforts. Norquist began his campaign for the complete demolition and removal of the Park East and its replacement with a landscaped boulevard in 1998, attempting to free up a sizeable tract of land for development. After studies which noted the removal of this incomplete freeway spur would not have a major impact on street congestion in the area and confirming its potential for economic development, the idea began to gain momentum. Norquist had to win the support of WisDOT, which controlled the highway as a state trunkline. In April 1999, the governor, the Milwaukee County Executive and Norquist, as mayor, all agreed to a wide-ranging set of transportation initiatives, one of which included the removal of the Park East spur. In June of that year, the special Milwaukee County panel examining the issue voted unanimously in favor of the demolition and the full county board approved the measure at their June 17th meeting.

With plans progressing on the demolition of the Park Freeway East, a proposal to scale back the freeway from ending at N 4th St to terminating two blocks earlier at N 6th St surfaced in April of 2000. The main reason for such a proposal was to free up yet additional developable land, though added costs and the additional time needed to demolish the extra segment of freeway caused concerns among city officials and local business leaders. The proposal eventually passed and two additional blocks of the freeway were added to the demolition schedule. Not everyone was happy with the plan, most notably downtown merchant George Watts, who filed a lawsuit in an attempt to block the removal of the freeway spur and even challenged Norquist in the 2000 mayoral election. Watts not only lost the mayor's race, but in March 2002, a federal judge threw out his lawsuit as well.

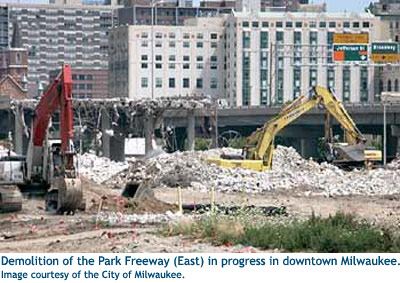

Demolition of the Park East began in June 2002, although the freeway remained

partially open to traffic in both directions. The elevated westbound lanes

of the freeway were demolished first beginning on June 2, 2002, leaving the

eastbound structure in place temporarily with one lane of traffic in each

direction. The eastbound lanes (carrying both directions of travel) were

then closed and razed in 2003 with major construction on the replacement

city streets lasting through 2004. From the Hillside Interchange, the former

Park East was replaced by a divided roadway ramping down to an at-grade intersection

with N 6th St, where state jurisdiction over the route now turns southerly

via 6th instead of continuing to the east via the former Park East corridor.

From N 6th, the road continues easterly as the four-lane W McKinley Ave boulevard

to a new lift bridge spanning the Milwaukee River and then connecting into

E Knapp St.

Demolition of the Park East began in June 2002, although the freeway remained

partially open to traffic in both directions. The elevated westbound lanes

of the freeway were demolished first beginning on June 2, 2002, leaving the

eastbound structure in place temporarily with one lane of traffic in each

direction. The eastbound lanes (carrying both directions of travel) were

then closed and razed in 2003 with major construction on the replacement

city streets lasting through 2004. From the Hillside Interchange, the former

Park East was replaced by a divided roadway ramping down to an at-grade intersection

with N 6th St, where state jurisdiction over the route now turns southerly

via 6th instead of continuing to the east via the former Park East corridor.

From N 6th, the road continues easterly as the four-lane W McKinley Ave boulevard

to a new lift bridge spanning the Milwaukee River and then connecting into

E Knapp St.

While the Park East Freeway demolition removed the freeway from east of the I-43 Hillside Interchange easterly, one small remnant of the Park Freeway remained: the Hillside Interchange itself. Built in the 1960s as a high-volume, freeway-to-freeway junction, the interchange with its left-hand entrances and exits and missing connections was itself eyed for reconstruction. Work began on the nearby Marquette Interchange project in 2004 with major construction commencing in 2005 and with that, the segment of the I-43/North-South Freeway heading north away from the Marquette to and including the Hillside were included in the project. On January 23, 2006, the all-new four lane boulevard connecting Fond du Lave Ave on the west and McKinley Blvd on the eat through the former Hillside Interchange was opened to traffic. The old freeway-to-freeway junction had been removed and replaced with a simpler and more traditional diamond interchange. This more appropriately-sized interchange also allowed for all the necessary movements between the STH-145 route and I-43, as well as eliminating the unsafe left-hand merges which were beginning to cause problems.

Thus, after 38 very contentious years, the Park Freeway officially passed into history.

Note: The map below will be updated in the near future to show the many route designation changes from 2015.