Wisconsin's Interstates

Wisconsin's Interstates

This page attempts to provide information about Wisconsin's portion of the Interstate Highway System not available elsewhere in these pages. In an attempt to provide a reasonable amount of information in a minimal amount of time, much of the information below is excepted from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation's excellent book "A History of Wisconsin Highway Development, 1945-1985" published in 1989 by WisDOT and compiled by George Bechtel. Additional information, both historical and current, will be added here in the future.

Questions, comments, corrections and suggestions are always welcome at chris.bessert@gmail.com.

From "A History of Wisconsin Highway Development, 1945-1985" by George Bechtel, published 1989 by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation:

The Interstate Emerges

The advent of the Interstate system added an entirely new dimension to almost all aspects of Wisconsin roads. And the Wisconsin Interstate story was classic "good news-bad news."

The Interstate concept is described in a rare document published January 12, 1944, in a message from President Roosevelt to the Congress. Significantly, this booklet contained a relief traffic map showing certain routes that, in Wisconsin, approximated the I-90 and I-94 corridors long before route decisions had been made.4

The State Highway Engineer, in 1945, submitted tentative route designations that included the currently used I-94 in southeast Wisconsin plus the Highway 18 zone between Madison-Prairie du Chien; Highway 51 northerly from the present Interstate toward Hurley; Hwy. 53 between Eau Claire-Superior; a route between Milwaukee-Green Bay; and an east-west loop between Green Bay-Eau Claire where it would have linked with the present I-94.5

The first Washington response was to substitute Tomah-La Crosse for Madison-Prairie du Chien. Other responses followed.

In the meantime, the Turnpike Commission, established by Wisconsin Laws of 1953, was looking over the situation.

Wisconsin had anticipated the Interstate, in a way, with studies of a possible toll road-turnpike. Consulting engineers from Baltimore, Md., and New York City in 1954 submitted, respectively, a preliminary engineering statement and traffic-revenue study.

The latter concluded that a toll road between Hudson and Hwy. 41, the Hwy. 29 loop, would be "cost beneficial" for motorists and profitable for the state.

The Maryland consultant's study looked at routes in the present I-90/94 corridor, except Tomah-La Crosse, along with a loop between Madison-Wisconsin Dells through Sauk City and another connecting Hwy. 41 near Kenosha through Burlington and Fort Atkinson to Madison. This study inferred that parallel routes might reduce potential tolls and lead to unprofitability.6

In June 1955, the Turnpike Commission reported to the Legislature that the Illinois-Wisconsin corridor was not feasible at the time and recommended delay "until future developments can be fully appraised."

Another toll road study was conducted at the State Legislature's request in 1982. Both a cursory Departmental analysis and a consultant's subsequent assessment reached negative conclusions.7

Meanwhile, Washington-Madison negotiations continued. In 1955, assuming

that there would be 2,400 miles of urban additions to the Interstate system,

the Commission asked for four more sections in the city of Milwaukee. This

included a loop around the central district, Howard Avenue-South 44th Street,

a 2.3 mile extension toward Glendale, and a 7.3 mile extension toward Hwy.

100.

Meanwhile, Washington-Madison negotiations continued. In 1955, assuming

that there would be 2,400 miles of urban additions to the Interstate system,

the Commission asked for four more sections in the city of Milwaukee. This

included a loop around the central district, Howard Avenue-South 44th Street,

a 2.3 mile extension toward Glendale, and a 7.3 mile extension toward Hwy.

100.

Letter exchanges continued in 1956 with requests for extensions into Madison, La Crosse, and Eau Claire—all denied.

Other decisions came in December. Washington denied the state's request for a route between Genoa City-Beloit, opting instead for Madison-Janesville-Beloit. A Milwaukee-Green Bay (Hwy. 41) route was approved, but the state failed to get plans completed in time to meet a deadline and the effort failed, according to G. H. Bakke, a legislator at the time.

The Commission made another try in March 1958 for additional mileage between Marinette-Milwaukee. This was denied is less than a month.

In February 1963, a request was submitted for a route between Milwaukee and Superior by way of Green Bay, Wausau, Hurley and Ashland. The additions, the covering letter said, could be done in "increments, if necessary: Milwaukee-Green Bay, Green Bay urban extension, Green Bay-Wausau, Wausau-Superior." Except for Milwaukee-Green Bay [in 1972] this, too, was deined.8

Nearly a decade later, still another try was made. In separate booklets, emphasizing necessary connections, the Department of Transportation asked for approval of Interstates between Milwaukee-Beloit and Milwaukee-Janesville; for connections again via Hwys. 52[sic] and 53 to the northlands, for the east-west (Hwy. 29) freeway, for extensions southerly in the Milwaukee area, for Green Bay-Milwaukee, and the Airport Spur.9

The Green Bay-Milwaukee (now I-43), the Lake Freeway (I-794), and Airport Spur extensions were subsequently approved. From what had been some 480 miles of Interstate, the Wisconsin system became 578 miles.

Immediately ahead lay controversy about the location and numbering of the Milwaukee-Green Bay route. The first proposal was a Hwy. 57 corridor about midway between Hwy. 141 along Lake Michigan on the east and Hwy. 41 through the Fox Valley to the west. The ultimate compromise was to use most of existing Hwy. 141 between Milwaukee-Sheboygan, then to angle mostly on new location between Sheboygan-Green Bay, and to call it I-43.

The final Wisconsin Interstate project was authorized in 1985 in the form of an I-43 ramp connection in Sheboygan.10

In a concluding word about the Interstate discussion to this point, state statistics supported claims for more corridors. As a two percent state (population, vehicles, other common indicators) but with only a shade over one percent of the national Interstate mileage, Wisconsin authorities felt deprived.

They also felt Wisconsin met all of the criteria for Interstate corridors: serving national defense; integrating the national system by filling missing links; assisting industrial, recreational and commercial movement, and "providing direct access to, for, and from rural and urban areas."

Apparently, being tucked away from major east-west and north-south routings, perhaps lacking enough aggressiveness, and being out of federal political favor at the wrong times, were handicaps too great to be overcome by logic.

At the same time, there was evidence of limited foresight and apathy, according to Bakke.11

Bakke added that lack of state vision and local enthusiasm—especially in Madison—also contributed to the shortchanging of the state. He noted the Turnpike Commission estimated Beloit-Madison traffic would reach 4,000 by 1980. In reality, it was 16,000-plus.

More About Interstates...

In 1966, the Interstate cost estimates required by federal authority indicated the cost for completion—not including the I-43 segment—would be about $509 million. 1z

When completed in 1981, except for the latest I-43 ramp near Sheboygan and the Lake Freeway in Milwaukee, the total cost for 1,381 separate Interstate projects was $900 million. 13

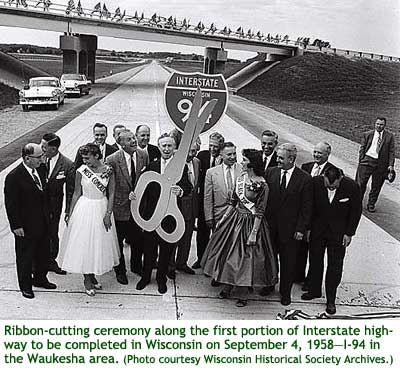

Wisconsin started Interstate construction in 1956 between Goerke's Corners and CTH-SS in Waukesha County, completing it two years later.

Between 1959 and 1969, more than three-fourths of the state system was built, including the East-West and North-South Milwaukee freeways (I-94), and the Milwaukee bypass (I-894).

In 1969, Wisconsin completed its initial rural Interstate at a time when only 70 percent was completed throughout the U.S.

This completion was made possible by the Accelerated Highway Improvement Law adopted in 1966. Citizen groups from throughout the state, the Legislature's own Highway Advisory Committee, and planning, engineering, traffic, and roadway studies all supported enabling Legislation. 14

Support for the legislation rose in a variety of other sources. One of the most powerful, John Wyngaard—long-time dean of the capitol newspaper correspondents—proclaimed "good roads are worth debt." 15

Even the American Automobile Association (AAA), usually an opponent of increased road revenues, got behind the effort after a survey of members. 16

Technically, the Commission could not borrow. The money was actually obtained "through lease agreements with nonprofit-sharing corporations"—the device used until a statewide referendum later authorized direct sale of bonds.

"Completion" is a misnomer, of course. The eternal dynamics of highways, with deterioration starting the moment of dedication to public service, probably applied more to Interstates than any other roadway.

When Wisconsin's Interstates reached the 20-to-25-year-old plateau in 1983, they were ripe candidates for reconstruction. The first to be reconstructed was I-94 in Kenosha County, where lanes were added to the heaviest travelled "rural" segment in the nation, and in Dunn and St. Croix counties. Those segments had been opened in 1959.

Reconstruction of I-90/94 between Madison-Portage, with addition of third lanes, was completed in 1984. That section had been in service since 1961. More work was also imminent on I-90 between Madison and the Illinois state line. The original segment of the system in Waukesha County was reconstructed in 1985.

Innovative concrete recycling was pioneered on I-94 west of Eau Claire, an extension of the process used to recycle bituminous surfaces starting in 1979—in which Wisconsin also has lead the nation.17

Perhaps an anonymous engineer's poignant statement made around 1965 best describes the Interstate.

"An ideal road may appear almost within reach but never quite attainable," he said. "The Interstate comes close." 18 19

FOOTNOTES:

4 Interregional Highways, A Message from the President of the United States,

1944

5 Correspondence re Interstate, 1963 compilation

6 Highway Advisory Committee: History and Activities, 1948-1977, pp. 34-35

7 Letter: Secretary Ayres-State Senator Cullen, Jan. 26, 1982

Letter: Secretary Jackson-State Senator Lee, Sept. 24, 1985

8 Proposed Extensions, Interstate Highway System, 1963

9 Missing Links in the Wisconsin Highway System, DOT presentation to FHWA, 1972

10 Federal Government Authorizes...Last Interstate Project Release, July 11,

1985

Map: The National System of Interstate and Defense Highways with statistics,

Dec. 31, 1983

"Interstates Now Main Street, U.S.A.," St. Paul (MN) Pioneer Press

and Dispatch, Sept. 8, 1985

11 G. H. Bakke Interview, December 1985

12 Wisconsin Interstate System Financing, SHC, April 1966

plus Interstate Cost Estimates in Central Files

13 "Last of the Interstate Projects," Western Builder, Aug. 15, 1985

14 Accelerated Arterial Construction (proposal), SHC, May 1966

Legislators Discuss Acceleration, Highway Communicator, May 18, 1966

Public Hearings Discuss Acceleration, various highways with reasons

"Acceleration vs. Non-Acceleration..", prepared for the Legislature

by Ronald J. Vogel, sponsored by UW-Madison, May 1966

15 "Good Roads Worth Debt," John Wyngaard, Wisconsin State Journal,

May 28, 1965

16 Special Presentation, Wisconsin AAA Motor News, May 1985 (with memo G. H.

Bakke to Counties)

17 "Recycling Pavements Saving Money, Energy, Materials," DOT release,

July 18, 1980

18 Address, W. F. Steuber, 1957

19 Appendix "O," Wisconsin Interstate Highways list; Appendix "P," Wisconsin

Freeways