Milwaukee Freeways

Freeway Pages:

• Airport Freeway

• Airport Spur Freeway

• Bay Freeway

• Belt Freeway

• East-West Freeway

• Fond du Lac Freeway

• Lake Freeway

• North-South Freeway

• Park Freeway

• Rock Freeway

• Stadium Freeway

• West Bend Freeway

• Zoo Freeway

• System Map

The story of the genesis, development, construction, halting and the mere existence of the Greater Milwaukee freeway system is a dramatic one, laden with excitement, promise, energy, grief, anger, betrayal, emotion of all kinds, and even a small bit of compromise. Milwaukee is not alone in North America as a city which, in the mid 20th Century, experienced dramatic growth, fraught with traffic congestion, and sought to relieve that congestion in the manner it best knew how: freeways. Many cities the size of Milwaukee and larger proposed major freeway networks linking their downtowns to suburbs, industrial areas, airports and to the Interstates being constructed between the major cities at the time. And, yes, what happened in Milwaukee also happened elsewhere—Boston, Washington D.C., Memphis, San Francisco—but the story here had its own unique twists and turns as well.

One could easily argue that an entire book could or should be written on the subject of Milwaukee's freeway system. Indeed, Richard W. Cutler, who has been partner at Quarles & Brady, member of the Fox Point Planning Commission, Brookfield city attorney, and member of the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC), has written an entire chapter ("Transportation Planning and the Freeway Wars") in his excellent book "Greater Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View," published in 2001 by the Milwaukee County Historical Society. Cutler's book served as one of several excellent sources of information for this and related articles and is a must-read for anyone interested in Milwaukee's storied freeway past. This article and those on each of the individual Greater Milwaukee freeways, however, are meant to be overviews and not comprehensive by any means.

Contents: The Early Years | Freeway Building Begins | Opposition Grows | The Seventies: An Impasse | Expressway Commission: End of the Line | John O. Norquist: Freeway Foe | Modern Times: Trials & Tribulations | The Future | Additional Information & Resources

The Early Years

The post-World War II era in the United States saw increases in just about

everything: population, economy, jobs, growth... automobile usage. Continuing

the trend begun well before the war, automobile ownership and use continued

to skyrocket and other forms of transportation—passenger railroad,

interurban, trolley/streetcar, bus—were all in decline. Suburbs were

growing, partly from city dwellers moving out to experience "country

living" or from G.I.s returning from the war needing places to live

and raise their new families. But jobs and, for the most part, major shopping

areas were still downtown and with more and more people having to drive to

those jobs and stores in automobiles, the major streets in all cities were

becoming overloaded. So, too, was the case in Milwaukee, where city traffic

grew a staggering 100 percent between 1945 and 1952.

The post-World War II era in the United States saw increases in just about

everything: population, economy, jobs, growth... automobile usage. Continuing

the trend begun well before the war, automobile ownership and use continued

to skyrocket and other forms of transportation—passenger railroad,

interurban, trolley/streetcar, bus—were all in decline. Suburbs were

growing, partly from city dwellers moving out to experience "country

living" or from G.I.s returning from the war needing places to live

and raise their new families. But jobs and, for the most part, major shopping

areas were still downtown and with more and more people having to drive to

those jobs and stores in automobiles, the major streets in all cities were

becoming overloaded. So, too, was the case in Milwaukee, where city traffic

grew a staggering 100 percent between 1945 and 1952.

While the concept of freeways were new to the average person in the early

1950s, they had been around and well-known in transportation planning circles

for many years. Aside from Germany's Autobahns, parkways had been built in

several American cities beginning in the 1920s and 30s and freeways, then

generally called "expressways," had also begun to show up on the

landscape in Michigan and California. In 1951, the City of Milwaukee hired

traffic consultants Amman & Whitney to study the traffic needs of the

city and report back their findings. A year later, they proposed a 20.4-mile

long expressway system for an estimated total cost of $150 million.  The reasons

for such a system were many: escalating operating costs were being borne

by citizens, there were rapidly increasing delays and numbers of accidents,

additional congestion would only bring additional losses and even depreciation

in property values. The plan was approved by the Milwaukee Common Council

and Mayor Frank Zeidler later in 1952.

The reasons

for such a system were many: escalating operating costs were being borne

by citizens, there were rapidly increasing delays and numbers of accidents,

additional congestion would only bring additional losses and even depreciation

in property values. The plan was approved by the Milwaukee Common Council

and Mayor Frank Zeidler later in 1952.

Indeed, even before bringing Amman & Whitney on board, Jim Casey, a student of the Milwaukee freeway system, notes city residents were asked to approve a $5 million bonding program to begin construction on expressway-type improvements in 1948. While voters passed this early measure, they were again asked for an additional $3 million in bonding in 1953, which passed with an even greater margin. These would not be the only votes on the Milwaukee freeway system, however the outcome of all votes would never change.

Construction quickly commenced and in 1953, the first 2,200 feet of freeway was completed in the South 43rd St corridor northerly from STH-59/National Ave to Wells St. It was dubbed the "South 44th Street Expressway" at the time, but was later incorporated into the Stadium Freeway. Later in 1953, sensing other municipalities would likely fight freeways that the City of Milwaukee wanted to punch through them, the city turned over the entire process and much of their staff to the newly-created Milwaukee County Expressway Commission. The commission was created in 1953 to plan, acquire right of way for and construct an expressway system and mass transit facilities in Milwaukee County" and to "coordinate planning with other agencies until completed..." The State Highway Commission then took over the actual construction and maintenance of the system.

Freeway Building Begins

One of the first orders of business of the new Milwaukee County Expressway Commission was to create an overall freeway plan for the area. On February 24, 1955 the plan was released expanding on the City's original ideas with a cost of $221 million and projected completion by 1972. It took into account civil defense needs, stating, "The evacuation of the county in the time of enemy attack can be greatly facilitated by the Expressway System. The wide, continuous rights-of-way (also) provide fire-breaks in the event of bombing." Recall, this was taking place during the beginning of the Cold War and attacks from foreign powers were at the forefront of Americans' minds. Indeed, the plan included a Nike missile base to be positioned beside a low-level drawbridge at the site of today's Hoan Bridge. The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel reports those missiles were actually present for a short period in the 1950s. The 1955 expressway report states, "At its connection with the proposed southward extension of Lincoln Memorial Drive, there would be provided a directional traffic interchange. The planning of this interchange and the proposed guided missile launching site has been coordinated."

Just over a year after the 1955 report, the Interstate Highway Act was signed

into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, creating the now ubiquitous Interstate

Highway System. This new system of highways meshed perfectly with the new

Milwaukee County expressway system and two of the freeways were incorporated

into the Interstate system—Airport and East-West—with parts of

two others included—North-South and Zoo. Additional segments of the

freeway system would eventually be incorporated into the Interstate system

in later years.

Just over a year after the 1955 report, the Interstate Highway Act was signed

into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, creating the now ubiquitous Interstate

Highway System. This new system of highways meshed perfectly with the new

Milwaukee County expressway system and two of the freeways were incorporated

into the Interstate system—Airport and East-West—with parts of

two others included—North-South and Zoo. Additional segments of the

freeway system would eventually be incorporated into the Interstate system

in later years.

After work had begun on the system, the newly-created Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC) stepped into the transportation-planning process and in 1965 crafted a comprehensive regional plan for freeways which the Milwaukee County Expressway Commission, the State Highway Commission and the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads would follow for the design and construction of the system. Many, including Richard W. Cutler, peg this as the high-point in the freeway-building craze. Opposition was minimal and between 1962 and 1967, an average of 9.5 miles of freeway were completed and opened to traffic each year. At the end of that time period, the county-level agency charged with helping to coordinate construction of the system was slightly renamed the Milwaukee County Expressway and Transportation Commission.

At this point, plans called for the construction of thirteen freeways in the greater Milwaukee area. They included:

- Airport Freeway – from the North-South Freeway near the airport westerly to the Zoo and Rock Freeways.

- Airport Spur – a short connector freeway from the North-South Freeway into the General Mitchell International Airport.

- Bay Freeway – from the North-South Freeway north of downtown westerly into Waukesha Co toward Oconomowoc.

- Belt Freeway – an "outerbelt" bypass of sorts, beginning at the Fond du Lac Freeway in Germantown and proceeding southerly through eastern Waukesha County, then turning southeasterly and easterly through southern Milwaukee County, ending at the Lake Freeway.

- East-West Freeway – from the Lake Freeway on the lakefront downtown westerly toward Waukesha.

- Fond du Lac Freeway – from Stadium and Bay Freeways northwesterly toward Fond du Lac and the Fox Cities.

- Lake Freeway – from just northeast of downtown Milwaukee southerly parallel to Lake Michigan through the southern suburbs, past Racine and Kenosha to a connection with a similar freeway in Illinois leading toward Chicago.

- North-South Freeway – from Ozaukee County southerly, running somewhat inland of Lake Michigan, passing downtown Milwaukee to the west and continuing southerly through Racine and Kenosha Counties to a connection with Illinois' Tri-State Tollway.

- Park Freeway – from the Lake Freeway on the lakefront downtown westerly to a connection with the Stadium Freeway.

- Rock Freeway – from the junction of the Airport and Zoo Freeways southwesterly toward Beloit.

- Stadium Freeway – from the North-South Freeway in Ozaukee County southwesterly, passing Cedarburg and Thiensville to the west, then southerly into Milwaukee County through the western neighborhoods of the city and ending at the Airport Freeway.

- West Bend Freeway – branching off the Fond du Lac Freeway and heading northerly toward West Bend.

- Zoo Freeway – from the Fond du Lac Freeway in northwest Milwaukee County southerly to the Airport and Rock Freeways.

Opposition Grows

The first organized opposition to a proposed freeway surfaced in September 1965 and was a harbinger of things to come. A public hearing was held for the proposed Lake Freeway segment through Juneau (now Veterans) Park. This segment of freeway was the eastern "side" of the rectangle of freeways which was to have enclosed the downtown core—North-South on the west, East-West on the south, Park on the north and Lake on the east—and was commonly referred to as the "downtown loop closure" freeway, as the other three "sides" were already complete or under construction. Four years later in 1969, however, vocal opposition was firmly entrenched and the Milwaukee County Board halved their contribution to the freeway system. Annual miles of freeway opening, which sat near ten just two year prior, fell to 1.9 at this time.

In April 1967, a referendum put before Milwaukee County voters asked if the "downtown loop closure" and the Lake Freeway South should be completed. Jim Casey again notes, "The anti-freeway members of the County Board had the question written so that freeway supporters had to vote 'no' on the question. Despite this, these freeways were passed by a near 2-1 margin." For a third time, when asked through a public vote, a majority of county residents supported moving forward with the freeway system.

While there were many sources, one of the major reasons for the growing opposition, however, was lack of advance public notice, according to Cutler. He noted that the Expressway Commission was often tight-lipped about the specifics of the freeways plan and another publication stated the group often "rode roughshod" over the proceedings. Cutler said:

For example, in early years, legislative and administrative action favored freeway construction over the interests of homeowners in several respects. The exact centerline location and width of the proposed freeway were not disclosed until the public hearing. By then, it was too late for affected landowners to offer comment that conceivably might alter the route. Earlier disclosure and dialogue might have yielded constructive suggestions from those directly affected. More likely, earlier notice might have lessened their feeling that the government was arbitrary, inhumane, and needed restraint.

Cutler also notes Herbert Goetsch, Milwaukee's public works commissioner in the 1960s and 70s, stated that Congress may have "saved the construction of the later abandoned freeways by authorizing the payment of 115 percent of the market value of the homes acquired." Families being evicted from their homes were often given the market value price for their homes at that moment, which was generally quite depressed, as the proposed freeway had quickly deflated prices for land and homes directly in the highway's path.

On top of the growing opposition to the freeways in the late 1960s, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969 required that all federally-funded projects have environmental impact statements prepared. While admirable in intent, Cutler notes many of the opposition groups turned this law into a weapon. One such group, the Citizens Regional Environmental Coalition was formed in c.1970 to fight the freeways in a more united manner. According to Cutler, the coalition's main points were that the freeways divided neighborhoods, they were primarily intended for suburban commuters to reach their jobs faster, and to also facilitate the evacuation of industry from the cities to the suburbs. Coalition-supported candidates ran for various public office and many were elected, drastically changing governmental tone toward the freeway-building process. While a majority of the public in the region—and, indeed, in the City of Milwaukee—still favored the completion of the freeway system as planned, their formerly public enthusiasm was more than drowned out by the voices of those opposed to the highways.

The public hearings for the proposed freeway projects became much more heated affairs as the construction of the system moved forward. In the volume "Wisconsin Highways 1945-1985" published by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, George Bechtel recounts one of the more contentious hearings:

A meeting at Custer High School in Milwaukee was one of the classics. Debating factions filled the school auditorium for an afternoon and an evening while closed circuit television carried the proceedings to nearby rooms.

Despite the efforts of an experienced presiding officer, Joseph Hutsteiner of the Milwaukee County Board, the hearing took on the tone of an athletic event with proponents and opponents alternately cheering and booing witnesses as they testified for or against the proposals.

Another hearing, at Grafton, was cancelled by a bomb threat. Others were picketed.

The Seventies: An Impasse

By 1974, of the 112-mile approved freeway system, only 61 miles were completed, accounting for 54 percent of the actual lane-miles and 69 percent of the carrying capacity. This included the North-South, East-West, Airport and Zoo Freeways. Seventeen miles, or 15 percent, of the system was scheduled for completion, including the Park, Stadium South and downtown loop freeways. The remaining 34 miles, or 30 percent, were not yet scheduled or budgeted, but were simply lines on planning maps. These unscheduled freeways, however, were important in that their existence and carrying capacity was assumed when planning and constructing the other freeways.

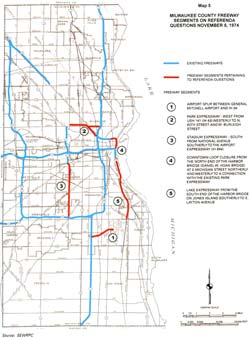

In

the mid-1970s, an impasse had developed between the pro- and anti-freeway

forces. On November 5, 1974, a set of five county-wide advisory referenda

were held, asking voters their opinion on whether five segments of freeway—or

the 17 miles scheduled and budgeted but stalled—should be completed.

These segments were the Airport Spur Freeway;

the Park

Freeway West from

the North-South to the Stadium

Freeway North; the Stadium South Freeway from STH-59/National Ave

to I-894/Airport

Freeway; the Lake

Freeway portion of

the "Downtown Loop Closure" from the eastern end of the Park

Freeway East to the lake then southerly to the junction of the East-West

Freeway;

and the Lake Freeway South from the Hoan

Bridge southerly to Layton Ave.

All five freeway segments passed the referendum, although opponents charged

ahead unfazed by the results. Cutler, in his book, even notes that in three

of the five wards in which freeways were proposed, the freeways won a majority

of the votes and, additionally, those three wards were represented by the

three most vocal freeway opponents! For a fourth time, the voters of Milwaukee

County approved moving forward with construction on the freeway system.

In

the mid-1970s, an impasse had developed between the pro- and anti-freeway

forces. On November 5, 1974, a set of five county-wide advisory referenda

were held, asking voters their opinion on whether five segments of freeway—or

the 17 miles scheduled and budgeted but stalled—should be completed.

These segments were the Airport Spur Freeway;

the Park

Freeway West from

the North-South to the Stadium

Freeway North; the Stadium South Freeway from STH-59/National Ave

to I-894/Airport

Freeway; the Lake

Freeway portion of

the "Downtown Loop Closure" from the eastern end of the Park

Freeway East to the lake then southerly to the junction of the East-West

Freeway;

and the Lake Freeway South from the Hoan

Bridge southerly to Layton Ave.

All five freeway segments passed the referendum, although opponents charged

ahead unfazed by the results. Cutler, in his book, even notes that in three

of the five wards in which freeways were proposed, the freeways won a majority

of the votes and, additionally, those three wards were represented by the

three most vocal freeway opponents! For a fourth time, the voters of Milwaukee

County approved moving forward with construction on the freeway system.

With the referenda essentially solving nothing, a group of the anti-freeway legislators and local university planners proposed a ten-year moratorium on all new freeway construction in 1977. While appearing to be attempting to compromise, Cutler notes the moratorium was merely another tool the freeway opponents were attempting to use to kill off the remaining freeway plans in Milwaukee. After first voting it down, the moratorium on freeway building was eventually accepted by SEWRPC late in the year, although, according to Cutler, the Milwaukee County Expressway Commission was rather unhappy and unsuccessfully requested that the federal grant money being sought by the City for housing in the essentially-abandoned Park Freeway West right-of-way be turned down.

Expressway Commission: End of the Line

In 1978, the construction of the Milwaukee area freeway system since 1950 had cost just over $400 million. The original 1955 estimate of $122 million for 45 miles of freeway had included $78 million for right-of-way acquisition and $143 for the actual construction work. The current Marquette Interchange reconstruction project (2004-2008) will cost approximately $800 million and the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel has pegged the complete reconstruction of the entire Southeastern Wisconsin freeway system at about $6.2 billion.

The Milwaukee County Expressway and Transportation Commission was abolished by the Laws of 1979, 26 years after it was created, with its powers and duties transferred to the Milwaukee County Board. As noted in the Wisconsin Department of Transporation's "Wisconsin Highways 1945-1985," "Reporting for its 1979-1980 biennium, the Commission said: 'Freeway construction in Milwaukee County has essentially come to an end . . . because of the reduction of freeway construction, the Commission directed its (concluding) attention to park-ride lot planning and construction, leasing of freeway airspace, general freeway maintenance activities, and varied special projects primarily related to safe operation of the freeway system." Continuing, it notes, "In a final report, Gordon King, the last chair of the Milwaukee Expressway and Transportation Committee, said: 'It is with pride and regret that we submit this final report. Pride in the many accomplishments . . . in bringing quality transportation facilities to Milwaukee County. Regret that the freeway system is left uncompleted with embarrassing "stub ends."'"

John O. Norquist: Freeway Foe

One of the major political forces which arose out of the late-1960s and

early-1970s fights of the Milwaukee area freeway system was John O. Norquist,

who was elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1975 based largely on

an anti-freeway campaign, and moved over to the state senate in 1983. From

Madison, Norquist sought to do everything he could to limit not only the

construction of new freeways in Milwaukee, but to also help block what were

perceived as improvements and increases in capacity for the system. Norquist

was then elected mayor of the City of Milwaukee in 1988 and immediately turned

his aim toward specific freeways and projects.

One of the major political forces which arose out of the late-1960s and

early-1970s fights of the Milwaukee area freeway system was John O. Norquist,

who was elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1975 based largely on

an anti-freeway campaign, and moved over to the state senate in 1983. From

Madison, Norquist sought to do everything he could to limit not only the

construction of new freeways in Milwaukee, but to also help block what were

perceived as improvements and increases in capacity for the system. Norquist

was then elected mayor of the City of Milwaukee in 1988 and immediately turned

his aim toward specific freeways and projects.

Soon after taking office, Norquist began his campaign to have the portion of the I-794/East-West Freeway through the downtown area removed and replaced by a landscaped, surface boulevard with traffic lights and direct access to businesses. The idea had come from an urban planning class at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee taught by the City's Planning Director, Peter Park (no relation to the Park Freeway). Park's class advocated removing the elevated freeway, which they said created a physical and psychological barrier between downtown and the Third Ward, and replacing it with an uncontrolled-access boulevard. Norquist took that idea and ran with it, but encountered severe opposition. Part of the opposition to Norquist's plan stemmed from the volume of traffic using I-794 in that area: approximately 89,000 vehicles a day, which could not possibly be handled by a surface boulevard. In addition, the STH-794/Lake Parkway was nearing completion, sure to increase the volume of traffic using that portion of freeway. (I-794's traffic volume in 2004 was up to 111,300, a 25 percent increase in five years.)

Norquist's attention soon turned away from the East-West Freeway and onto a much more likely target: the Park Freeway East, which had never been completed on either end and was now merely a stub freeway, likened to a long freeway off-ramp by many of its detractors. The Mayor claimed that demolishing the derelict, underutilized—it never connected to many of the other freeways it was supposed to—freeway "stub" would free up many acres of land for development and inclusion back on the tax rolls. With much lower traffic volumes than on the East-West Freeway and a study showing that its elimination would only increase the congestion on other downtown streets slightly, an opportunity fell into Norquist's lap: a chunk of federal transportation dollars needed to be spent by the state or it would be lost. So Norquist, Governor Tommy Thompson and Milwaukee County Executive Thomas Ament agreed to split the money amongst three major projects, including the demolition of the Park Freeway East. Norquist was finally able to exact revenge upon the freeways he had so actively campaigned against for nearly twenty years.

As he was nearing the end of his tenure as Mayor, Norquist again proposed modifying the Milwaukee area freeway system, although this time not suggesting any major physical changes. In his "State of the City" address on January 21, 2003, Norquist suggested eliminating the I-894 designation along the Airport and Zoo Freeways from the Mitchell Interchange to the Zoo Interchange. Then, he suggested I-94 could be transferred to the "bypass route" and I-794 could be extended westerly approximately five miles along the East-West Freeway to the Zoo Interchange. Norquist hoped that the simple act of renumbering the highways would cause more traffic to bypass the heart of the city, lessening volume not only on the two major freeways, but also through the Marquette Interchange. The Mayor, not only an opponent to the freeways themselves, was also opposed to any enlarging of the Marquette Interchange during its impending reconstruction. Like the plan to remove the East-West Freeway east of the Marquette a decade earlier, Norquist was still trying to minimize the presence of the freeways in his city. Most, however, doubted the flip-flopping of the route designations would have any affect and the numbers were left as-is.

Modern Times: Trials and Tribulations

During the ten-year moratorium (1977-1987) and for the decade following that when no additional freeway miles were constructed, traffic continued to mount on all Milwaukee area freeways, especially on the I-94/East-West Freeway, linking the Marquette Interchange downtown with the growing Waukesha Co suburbs, including Brookfield, Waukesha and Pewaukee. While the freeway debates of the 1960s and 1970s generally had two factions—for and against—the debate over how to alleviate the increasing pressure on the I-94 corridor created even more splinter groups.

In the mid-1990s, WisDOT commissioned a study to see what options were available and attempted to garner support for those which could provide the most help. There were those who favored adding more general purpose travel lanes to the freeway, some who advocated for high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, those who wanted a light-rail system installed, others who campaigned for additional bus service in the corridor and even some who liked any number of combinations of the above. Unfortunately, this put the powerful politicians, such as Waukesha Co Supervisor Dennis Finley, outspoken Mayor John O. Norquist of Milwaukee and Governor Tommy Thompson in opposite corners as each opposed at least some portion of the available alternatives that others supported. With traffic volumes continuing to climb and accident rates outpacing those of similar facilities, consensus has yet to be reached, with the sole exception of additional bus service, which has seen some success.

As Cutler so acutely points out in his book, traffic volumes have been steadily increasing over the decades and very little relief has come in that same time period.

The Future

Regardless of position on or attitude toward the freeways in Greater Milwaukee, a simple fact is that the freeway system is more than forty years old and experiences very heavy use. While existing maintenance efforts try to eke as much time as possible out of the existing pavements and bridges, it is clear the system will need to be reconstructed at some point in the future. Whether this reconstruction includes additional travel lanes, interchange ramps or freeway miles is up for debate, but the life of a freeway is, indeed, a finite one.

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has cited the freeway system in Southeastern Wisconsin as "probably the most significant preservation need in the state transportation system," also noting "its outdated designs raise serious safety concerns, while its rapidly deteriorating condition threatens to dampen the economic vitality of our entire state." The department further recognizes the Milwaukee area freeway system as the "heart" of Wisconsin's transportation system which serves as an economic backbone and commercial lifeline.

According to SEWRPC, a separate program for the rehabilitation and expansion of the freeways in and around Milwaukee was created as part of the 2001-2003 biennial budget. Later legislation prohibited WisDOT from using the appropriations for state highway rehabilitation or major highway development for any rehabilitation or capacity increases on the freeways of southeast Wisconsin. The first major project commenced under this new program is the complete reconstruction of the Marquette Interchange in downtown Milwaukee, to be completed in 2008 for a total of nearly $900 million.

A SEWRPC report noted that WisDOT indicated following the Marquette Interchange project, many other segments of the Greater Milwaukee freeway system would need similar reconstruction work and that a long-range plan prepared in 1999 by the department called for the reconstruction of the system to run twenty years from 2000 to 2020, adding lanes to 57 miles of freeway and costing an estimated $5.4 billion. SEWRPC then conducted a comprehensive study of the system and similarly recommended total reconstruction, but with additional lanes on 127 miles of freeway over thirty years (2001 to 2030), at an estimated cost of $6.25 billion.

It is clear something will have to be done with Milwaukee's aging freeway system and whatever path is chosen, it will cost a significant amount of money. And, thus, a freeway system borne out of necessity and desire, mired in controversy and dispute, will continue to be a source of discussion and debate into the future.

Additional Information & Resources

- Milwaukee Area Freeway System Map - clickable map showing all current, proposed, cancelled and removed segments of freeway in Greater Milwaukee.

- Afterword: The Politics of Congestion: The Continuing Legacy of the Milwaukee Freeway Revolt, Public Works Historical Society: Essays in Public Works History, October 2000 – (via archive.org) the thoughts of David F. Schulz who as executive director of the Infrastructure Technology Institute at Northwestern University is an astute observer of trends in public works and transportation infrastructure. Here Schulz offers his thoughts on the policy implications of the Milwaukee freeway experience.

"The

Politics of Congestion - Essay #20" by James J. Casey, Jr., JD –

purchase from American Public

Works Association. This case study examines the history of freeway

politics in Milwaukee City and County from public policy, legal, social,

and environmental perspectives.

"The

Politics of Congestion - Essay #20" by James J. Casey, Jr., JD –

purchase from American Public

Works Association. This case study examines the history of freeway

politics in Milwaukee City and County from public policy, legal, social,

and environmental perspectives. "Greater

Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View" by

Richard W. Cutler – purchase from the Milwaukee County Historical Society.

"Greater

Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View" by

Richard W. Cutler – purchase from the Milwaukee County Historical Society.- "Greater Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View" by Richard W. Cutler – from Amazon.com

- "Greater Milwaukee's Growing Pains, 1950-2000: An Insider's View" by Richard W. Cutler – page from the UW Press.

- Milwaukee's Freeway Past – from Craig Holl at midwestroads.com.

- Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission – home page.

- Route Listings: